This article will be feature in the ESG & Emerging Markets Sustainable Finance Special Report being published in September. Click here to receive a complimentary copy.

Measuring a borrower’s ESG – shorthand for environmental, social and governance – posture has in recent years become more important for investors looking to gain deeper insight into an organisation’s ethical and sustainability practices, often in the hopes of using this information to help avoid reputational or idiosyncratic risk events. It is particularly essential for those on the hunt for green bonds and other securities that claim to generate similar non-economic returns.

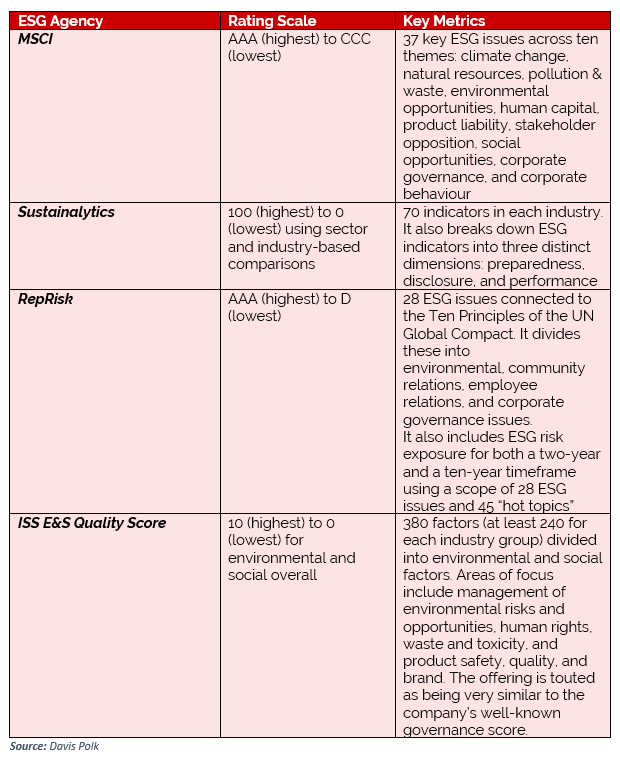

ESG rating services are used by many of the world’s largest investment funds and are growing more numerous; Bloomberg, Dow Jones, Institutional Shareholder Services, MSCI, RepRisk, Sustainalytics, SigmaRatings, and Thomson Reuters are just a handful of the dozens of specialist providers catering to rising demand for ESG analysis and rating. Traditional credit rating agencies like Moody’s, which recently launched a green bond-specific rating system aimed at measuring the management, administration, and allocation of use of proceeds on ESG-linked instruments, are also throwing their collective hat into the ring.

Lack of Standards

This veritable pick & mix in ESG rating and scoring has naturally led to varied adoption within the investing universe. BNY Mellon for instance has partnered with Sustainalytics to provide environmental, social and governance data on and to global issuers. BlackRock uses a combination of ESG data provided by MSCI along with its own data for its own ESG-focused ETF products.

JP Morgan, which has partnered with BlackRock on its recently launched ESG index (JESG) specifically aimed at emerging markets, claims to soak up data from Sustainalytics, RepRisk, and the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) as inputs.

It also applies another ethical screening on top of that, excluding sectors like Thermal Coal or ‘Clean Coal’, Tobacco, Weapons, or any violator of the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) principles. The JESG is available for the EMBI Global Diversified, GBI-EM Global Diversified and CEMBI Broad Diversified to begin with.

According to JP Morgan: “There are five components in the JESG methodology once the baseline index is selected: define the data inputs; establish JESG index scores; apply integration mechanics; consider ethical factors and exclusion, and calculate new ESG weights. These newly calculated JESG index scores will be systematically applied to determine the new ESG weights in the index, and issuers with better ESG scores will have their weights increased relative to their baseline index weights. The JESG suite will also overweight Green Bond issuances.”

A standardised approach to what constitutes a return in ESG terms is, however, sorely lacking, despite the flurry of activity around properly pinning down their measurement, making it more difficult for investors to compare securities’ and companies’ ESG practices in an unbiased way. Core ESG metrics considered by some of the largest rating houses can vary from anywhere between 12 to more than 1,000.

“Individual agencies’ ESG ratings can vary dramatically. An individual company can carry vastly divergent ratings from different agencies simultaneously, due to differences in methodology, subjective interpretation, or an individual agency’s agenda,” explains Timothy Doyle, Vice President of Policy & General Council at the American Council for Capital Formation (ACCF) in a recently published report, which analyses and compares different ESG rating providers.

Understanding, Overcoming Bias

There are also inherent biases – from market cap size, to location, to industry or sector – many if not all of them rooted in a lack of uniform disclosure, Doyle says.

These biases seem inherently difficult to address through quantitative modelling, and some experts are sceptical about how one would quantify certain factors. For instance, it is reasonable to expect that larger companies are better positioned to allocate resources into non-financial disclosure than smaller, leaner entities, thus increasingly the likelihood that larger companies will score higher in ESG terms.

Additionally, jurisdictions with more stringent non-financial reporting obligations (like Europe, which requires companies with 500 employees or more to publish non-financial statements and provide additional disclosures around diversity and sustainability) are likely to be home to entities that carry a stronger ESG rating than their peers based in regions where such reporting is optional, like the US or Indonesia.

Both of these factors skew the ESG rating scale in certain countries and industries in a way that disadvantages some – usually smaller – entities.

Doyle contends that because there are no standardised rules for environmental or social disclosures for ESG-linked instruments, nor any mandated disclosure auditing process to verify reported data, agencies have to rely on assumptions about the efficacy and tangibility of ESG-related impacts in their assessments.

“That lack of disclosure distorts the information available to both rating agencies and investors.”

EM Bias

Then there is the general emerging market bias present in ESG scoring, partly a function of the above, and partly the result of a broader psychological divide between developed and emerging markets that influences fuzzier qualitative factors like ethical posture or perceptions of corruption to more fundamental underlying factors like credit ratings.

“There are companies in Mexico and Argentina that are every bit as savvy when it comes to embracing ESG in practice and internal policy as their counterparts in Europe and the US, but many ESG rating agencies still treat emerging markets a bit homogenously, particularly when it comes to perceptions of governance,” explains John Bates, an emerging market corporate analyst at PineBridge in London.

“Whether on ESG or credit rating, one of the biggest anomalies is that most of the corporates in our universe, if they were literally lifted out of Brazil, or Colombia, or Russia, and implanted in the US, they would be A-rated companies. Our portfolio is roughly 50% investment grade and the average rating across the portfolio is BB or BB-.”

ESG profiling has been a big focus for PineBridge in recent years. The EM bond team relies exclusively on its own data, and uses 9 ESG factors against which each of the 400 entities his team covers are matched, ranging from binary box-tickable metrics like ‘is the company operating in the alcohol or firearms product segments?’ to others that are much more difficult to quantify, like ‘is the company ethical?’ or ‘how does management treat human capital?’.

“It can be tricky, especially when you are trying to compensate for natural discrepancies that emerge in certain sectors and in certain countries, or in countries that are handicapped by a legacy of poor investment,” he added.

Measuring the Unmeasurable

It is indeed quite difficult to take something qualitative like ethics and place it in a quantitative framework, Bates explains, but one of the ways this can be done is by separating out entities into respective peer groups aligned by sector, geography, size, and rank them relative to one another on an empirical basis.

This also helps contextualise borrowers against a myriad of factors that some external ESG score providers either don’t adjust for, or do adjust in peculiar or opaque ways.

For instance, from an ESG perspective, according to MSCI scoring, Petrobras would be excluded, but PEMEX wouldn’t. But if you look at RepRisk, the opposite is the case. So, there is definitely a difference depending on the provider and it isn’t always clear which of the variables either entity falls down on, explains Claudia Calich, who manages M&G’s emerging market bond fund.

It’s easier to normalise something like carbon emissions or green investment because you can compare to regional peers rather than global average and localise them to some extent. It’s much harder to do this from a governance perspective, or with perceptions of corruption, in a quantifiable way, and in a way that doesn’t lean on biases.

For example, many people have a sense of which countries may have more endemic corruption, as lofty as that may be… but look at something like the Freedom House Index – it’s an entirely different thing than saying country ‘x’ is 23% more corrupt than country ‘y’, she says. At the end of the day, there are so many indicators and components of scoring, and the results are not necessarily irrational… but they aren’t necessarily precise, either.

For ESG-centric investors, the variety in approaches aimed at assessing an entities approach to the environment, sustainability and governance isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For the savvier, more switched-on pockets of investors, it’s that variety which gives them the ability to choose exactly how they want to measure the non-financial benefits they aim to foster.

But investors also need to be aware that going into the murky world of ESG scoring without eyes wide open could lead to unmet expectations on the very non-economic benefits they aim to measure at best, or a misinterpretation of risk that could lead to a blow-out down the road at its worst.

This article will be feature in the ESG & Emerging Markets Sustainable Finance Special Report being published in September. Click here to receive a complimentary copy.