Fintech is a catch-all term for a huge number of new financial services, digital wallets, data analysis systems, money transfer technologies, stock market algorithms, start-ups, personal finance apps and many other elements that mean different things to people from different industries. Its roots lie in the Silicon Valleys and Tech Cities of this world, but its gaze is purposefully set on the emerging markets. With over 90% of the world’s under-30s living in emerging economies, these territories are the ideal beneficiaries of an industry that received more than US$19bn worth of investment over the last year – double the amount in 2015.

In terms of how these technologies spread, it is useful to draw parallels with global telecoms systems and digital technologies that rooted themselves deep in developing economies over the last decade.

Mobile internet penetration worldwide has doubled from 18% in 2011 to 36% today; by 2017, mobile access will exceed fixed-line access, with 54% penetration compared to 51% currently, according to the Alcatel-Lucent, a telecoms equipment manufacturer. There will be roughly 352 million Long Term Evolution (LTE, or 4G) connections in emerging markets by 2017 – roughly 10% of global mobile broadband. And by 2020, 12 of the top 15 smartphone markets will be in emerging economies.

4G/LTE (Fourth Generation / Long Term Evolution) is the next stage in mobile network development and provides users with much faster data speeds than 3G is able to. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU-R) set standards for 4G connectivity in March of 2008, requiring all services described as 4G to adhere to a set of speed and connection standards. For mobile use, including smartphones and tablets, connection speeds need to have a peak of at least 100 megabits per second, and for more stationary uses such as mobile hotspots, at least 1 gigabit per second.

According to the World Bank by 2017, roughly 87% of all broadband connections in emerging markets will be mobile. The spread of wireless connectivity is much faster than in many developed markets because lack of fixed communications infrastructure allows these countries to bypass the slow process of improving land-based connectivity.

Increasing mobile and online connectivity allows for faster communication, better quality of service, and more efficient governance. It also improves engagement, a driving force behind the distribution of new technologies and communication systems.

Big data and the spread of mobile technologies increases corporate and government transparency, removes bureaucratic blocks and helps to tackle corruption, while also making a host of industries more inclusive and accessible to broader segments of the population. This “digitalisation” of emerging markets is proceeding at warp speed. According to WB’s estimates, a mere 10% increase in broadband connectivity brings about a 1.4% bump to a country’s GDP.

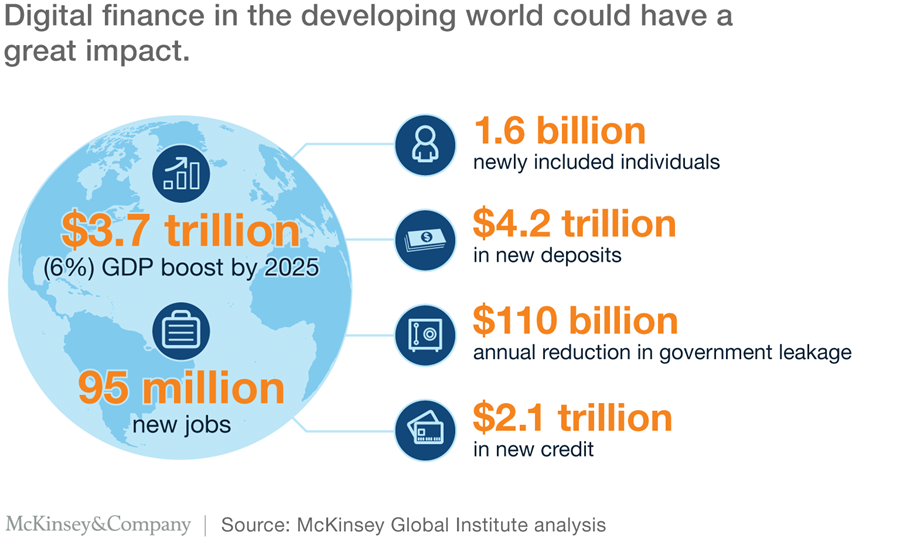

For Fintech, the same factors are in play. Low-cost financial services, according to McKinsey Global Institute estimates, could add 6% to emerging market GDP by 2025, equating to nearly US$3.7tn, generating up to US$2.1tn in extra lending to individuals and small businesses. The change could attract as much as US$4.2tn of deposits to financial services providers.

According to the report, governments could gain US$110bn per year by reducing leakage in public spending and tax collection, while other consumers stand to save US$400bn annually in direct costs by shifting from traditional to digital accounts, which can be 80% to 90% less expensive to service.

Regulating the Fintech Revolution

At the heart of many Fintech products and developments are innovative encryption systems, such as blockchain - a distributed database that maintains a continuously-growing list of ordered records called ‘blocks’ and maintains a high level of security through a system called decentralized consensus.

A blockchain is a database where a client can rely on the records/entries to be legitimate since falsifying them is expensive and requires consensus of other clients, not party to the transaction. The older an entry is, the more expensive it becomes to manipulate it. In a traditional database, the records can be manipulated by the administrator of the database at will. So, for a currency system like bitcoin, using such an administrate would entail inherent risk, so instead blockchain is used. It's a distributed ledger that is made in a way so that if a fraudulent transaction is attempted, or someone tries to "spend" the same token-of-value twice, the blockchain will by public consensus reject the transaction.

Encryption technologies have opened doors to a host of other Fintech innovations, from cryptocurrencies and instant money transfers, to mobile banking, credit checks and microfinancing. Many of these disruptive technologies already have a strong presence in the financial systems of the emerging economies, producing both cost-saving benefits and policy nightmares for consumers and governments, respectively.

Consider China and India, for example, two emerging market countries that now lead in Fintech. They share a huge online presence, significant skills in IT, a highly active user-base that is e-finance savvy, and a large number of early adopters.

In China, according to the country’s Central Bank, there were 6.317 billion mobile payment transactions in the second quarter of 2016, accounting for spending of CHY29.32tn (US$4.4tn), which represents an increase of 168.46% and 10.20%, respectively, from the year before. By 2015 there were 413 million online shoppers, with around 30% of the country’s vast population using e-payments and internet-based wealth management services.

But while these trends reflect a rise in standards of living and prosperity, they also create a dilemma for the Chinese government, which has been hit by massive capital outflows in recent months amid currency depreciation.

As an estimated total of over US$573.2bn streamed out of the country this year, the government continued desperately to plug the holes. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, offering anonymity, speedy transfers, and command little to no fees, quickly became one of the favoured means for capital holders to stash their money offshore.

Since August this year, the value of bitcoins have soared 70%, and reached US$792 per unit – a record high – with nearly 95% of global bitcoin trading today done through Chinese exchanges, according to digital currency research firm Coindesk.

The Chinese government, for now, is looking to curb outflows and regulate the cryptocurrency market, but the PBOC’s recent announcement that it is looking to launch its own digital currency suggests the state is prepared to accept the inevitable. If you can’t beat them, join them.

Bitcoin has also gained traction in India, but the main driver has been president Modi’s fumbled currency demonetization, which led to massive shortages of hard cash and also left few options for those who were not willing to take their under-the-carpet savings to the bank. The sudden removal of nearly 86% of all cash in circulation lead to mile-long queues outside banks, but it also boosted Fintech and money-transfer start-ups, such as Paytm or MobiKwik, which are popping up rapidly in India and beyond. In their first hour of operation after the demonetisation announcement, nearly US$2mn was added to Paytm accounts across the country — compared with an average of US$200,000 a day. Since then, 4 million people have signed up to use Paytm wallets, with service traffic rising 700%.

Modi seemed not only unfettered by the outflow, but actively encouraged it. “I want to tell my small merchant brothers and sisters, this is the chance for you to enter the digital world. Why don't we take first steps to making India a cashless society?”, Modi reportedly said in his monthly address to the media.

Admittedly, Modi’s apparent lack of concern about capital flows into the digital universe could in part be based on embarrassment over mishandling the demonetisation process. But, perhaps, the Indian leader sees the long-term benefits for the banking sector in a country where trust in banks is low and few have a personal bank account.

Everybody Wins

“There is a massive opportunity as banks in emerging markets are underserving local markets,” said EFL's Director of Innovation Kyle Meade.

According to the expert, returns on loans can be significant while still undercutting local predatory practices – giving investors access to high yields.

“Over time, this will balance out and returns will decrease but underwriting efficiency will increase. This means new lenders can start off lending with high rates while taking large risks and eventually reduce the interest as risk decreases,” Meade noted.

It is not just India and China, either. Mobile banking, a stable in places like the US and Europe, is becoming more prevalent across emerging markets, with lack of financial infrastructure often acting to the benefit of these new and innovative entrepreneurs, and allowing them to establish new platforms more quickly than they otherwise would in countries with developed market demographics.

Russia’s Tinkoff Bank, a pioneer in mobile banking, operates a disruptive internet-only business model which has seen the bank become a top two credit card issuer in Russia in less than 10 years. It remains one of the edgiest and most progressive FIs in the region, pioneering technologies like voice-based authentication, social-media based customer services, integrated Apple pay and new investment platform enabling customers to invest in securities online.

Tinkoff Bank’s success soon led to an emergence of a host of similar projects, such as Rocketbank, and also inspired more reluctant traditional banks to look into offering Fintech solutions. For instance, the Bank of Russia has developed and tested on an Ethereum-based blockchain prototype called “Masterchain” for financial messaging, to be used by other Russian FIs.

Another example is Monetas. A Swiss-founded start-up operating in North Africa, it uses the blockchain technology to provide a digital wallet, which allows people to transfer money and pay for goods without requiring a bank account. The company has teamed up with the Tunisian Postal Service for a pilot scheme that uses an electronic currency, dubbed the eDinar.

In the UAE, the Ministry of Finance (MoF), in partnership with National Bank of Abu Dhabi (NBAD), recently launched eDebit, a new e-Dirham service that allows payment of service fees and purchases through direct debit from the customers’ bank accounts and enables users to make online payment for more than 5,000 government services. And this October, the Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank (ADIB) has partnered with Fidor Bank to launch the region’s first “community-based digital bank, where users can exchange financial advice and also help co-create banking products.”

Meanwhile, in Dubai, several start-ups are beginning to exploit cryptocurrency capabilities. Beehive, a P2P lender launched in 2014, allows investors to lend to small businesses and it has so far lent over US$13mn.

Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, sometimes abbreviated P2P lending, is the practice of lending money to individuals or businesses through online services that match lenders directly with borrowers. Because such entities can run with lower overhead and provide the service more cheaply than traditional FIs, lenders often earn higher returns compared to savings and investment products offered by banks, while borrowers can borrow money at lower interest rates.

Latin America is also becoming a flourishing Fintech hub, with multiple promising start-ups emerging in recent years. One is Kubo Financiero, a Mexican start-up. It acts as a peer-to-peer lender that matches middle-income and wealthier savers with small businesses and households seeking to borrow between US$400 to US$4,000. Borrowers submit requests that are automatically risk-assessed along with their profiles, and lenders can select the borrowers they want to fund.

“Mexico is really exciting – there are some really cool Fintech companies that are balancing the Silicon Valley start-up style with emerging market insight. In Indonesia, we’re also seeing ‘old-school’ players like banks start to embrace Fintech,” Meade said. “This is putting pressure on traditional banks and microfinance institutions to adopt new technologies.”

And Africa – traditionally an exotic destination for investors – has been producing more exotic “frontier” Fintech products. For example, taking the concept of mobile banking a step further, Kenya recently launched the world’s first mobile bond called M-Akiba, allowing the country’s mobile users to invest in the KES5bn sovereign mobile infrastructure note.

Platforms like these could soon become commonplace, opening up a micro-trading market for middle-income individuals and SMEs that would not have previously invested in the bond market. Indeed, a report recently penned by the International Capital Markets Association suggests the traditional bond trading model, mostly reliant on market-makers and voice broking is being eroded.

“This is partly due to a natural evolution of bond trading driven by technological progress and the drive for cost efficiencies, resulting in an increasing electronification of markets and regulatory pressures undermining broker-dealers’ capacity to hold, finance, or hedge trading positions.”

The insurance industry is also likely to be transformed by Fintech in the coming years. Microinsurance is a low-cost and high-volume model, driven by mobile technology, where mobile data mining could help to set premiums and market-bespoke EM solutions.

While the insurance industry is heavily regulated in most countries, the technologies used in such models could see costs brought down significantly – namely, in operations, customer acquisition, marketing and distribution.

Investors around the world poured US$22.3 billion into fintech deals in 2015 – a 75% leap from 2014, and insurance technology, or insurtech, took up around US$2.6bn of that figure. With value of insurance assets globally reaching US$15tn, the market offers vast untapped potential for the gradually maturing Fintech industry.

Challenges Remain

Naturally, the emerging market landscape is highly promising, but also challenging in comparison with the developed countries. Meade points out a number of problems that Fintechs face when trying to penetrate these developing markets.

There are wider historical and cultural issues at play, particularly in the poorest regions.

“Prospective applicants are nervous of new players offering loans, for example, and tend to be sceptical. Familiarity with technology is also lacking in many places, so the user experience needs to be designed with great care,” Meade explained.

These challenges pile on top of the more universal structural and operational risks that disruptive technologies have brought anywhere they arrived.

Regulating money flows in digital and cloud-based systems is a daunting task for even the highest-profile, most technologically fluent FIs and Central Banks. Cyber-security needs to be improved, as numerous hacking attacks on banks and institutions this year have shown. Disruptions to traditional employment and business models are putting thousands of companies and millions of jobs on the line.

Nevertheless, the beauty of new technologies is that they may take with one hand and give with another; as they create problems, they offer solutions.

There is, of course, no secret recipe for success, especially in unpredictable EM environments. Young companies with a strong focus on a segment or specific business process seem to be get the earliest market traction. Their overall presence in the emerging market environment is soaring and, given the right conditions and support from local governments, financial technologies could become the key to healing global wealth gap between the prosperous 1% of the world’s population, and the less fortunate 99%.