Supply, or rather oversupply, is among the primary reasons for declining oil prices. Responsibility, or blame, lies with US shale oil producers and OPEC. In the US, the emergence of fracking led to a renaissance in the Midwest, specifically Texas and its neighbouring states. In addition to reviving economic growth and providing employment in the region, it led to the US becoming a net exporter of oil. As of December 2015, monthly US production of crude oil stands just 7% below peak historical levels (October 1970).

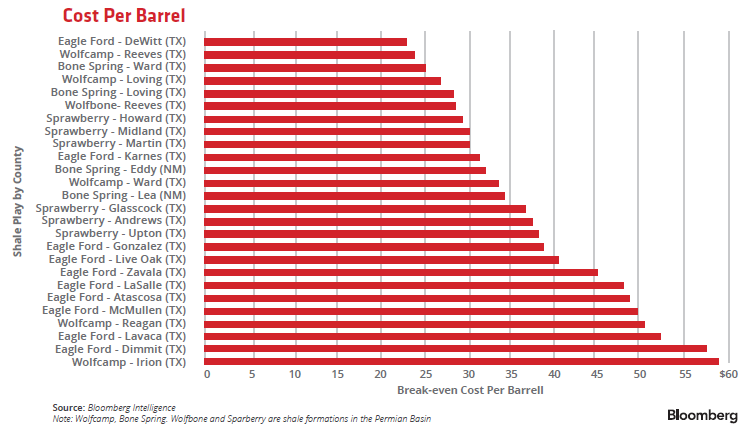

Given the plunge in oil prices, many analysts have cited an eventual decline in US oil production given their relatively high cost of production. In theory, the assertion has merits. In practice, it has yet to play out as US oil production remains close to all-time highs. The key is identifying break even costs for these producers. This is where most analysts’ assumptions have been mistaken. In some counties in Texas, the average well can still be profitable with oil at $22.5 per barrel. The low for the year, thus far, has been around $27. The wide range of breakeven costs, illustrates why production levels have yet to decline materially in the US. A logical follow up question would be to ask, why hasn’t the decline in production from unprofitable wells made its way in US production data?

Alternatively, why is US production still so high given that oil is far below many producers’ break-even price? The complication arises when we look at debt levels across the oil industry. The oil industry, and commodity producers at large, finds itself trapped in a ‘drill or die’ situation. During 2008-2011, commodity prices across the board rose exponentially. During this period, commodity producers took on extremely high debt levels in order to acquire or build additional production capabilities given rising prices and demand.

With oil having plummeted from over $110 in 2014, to $40 today, revenues and profitability have also crashed. Although many oil producers are losing money on each barrel of oil they sell, stopping production would result in halting the cash flow that is being used to satisfy debt obligations. In effect, to avoid bankruptcy or defaulting on their debt, oil companies need to keep producing oil at unprofitable levels. The solution to surviving in the current environment is simple: higher prices. However, in order to get higher prices, the market needs less supply. Less supply would result in defaults and bankruptcy. While this conundrum is comical, it is the harsh reality facing oil and commodity companies across the globe.

OPEC faces its own supply side issues. Incessant chatter of coordinated production cuts or halts, has led to large spikes in the price of oil, only to prove temporary. This time around, investors are hopeful that a meeting on April 17 will lead to a production freeze by OPEC and non-OPEC members. As a result, oil prices have rebounded from $27 to $40. Although an agreement may help rebalance the supply of oil in markets, the prospect of a large scale agreement is low given the geopolitical discord amongst members. Furthermore, Iran has been extremely vocal in its plan to increase supply by 500,000-1 million bpd. Current estimates suggest Iran has already increased supply by 350,000 bpd in 2016, with the goal of doubling that in the next few months. One can hardly blame them given the trends seen in OPEC and member countries’ oil production.

Given Iran’s intentions to increase oil exports to pre-sanction levels, bringing them in line with production trends of other OPEC members, the probability of Iran agreeing to a cut or freeze in production is extremely low. Envisioning a scenario where OPEC and non-OPEC members agree to limit production across the board while allowing Iran to gradually increase exports over time, are higher but still not a bankable outcome. The chances are further reduced by the recent pullout by Libya from the April meeting. Their reason is simple: to return to pre-conflict oil production levels.

Although supply is a pivotal issue facing oil markets, the flip side of the coin, which is demand, gets far less coverage. On a macro level, global growth is on a declining trend. China, the second largest economy, is at the epicenter of slowing growth resulting in lower commodity demand. Although China’s growth and currency problems have been the focus of many of my Research Notes, the key as it relates to oil is their trend in economic growth. Here, there is little doubt China is slowing.

Thus, incremental demand for oil and commodities in general, is slowing. Shifting focus to the US, which for many has been the leader of global growth, the economy faces strong headwinds as a result of a strong US Dollar and weak global growth. In 2015, economic growth slowed drastically from 3.9% in the second quarter to a paltry 1% in the fourth quarter. As illustrated above, the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank, the most accurate of US GDP forecasters, has brought down its estimate for US growth in 2016. Their current forecast for first quarter 2016 growth is 1.9%, down from over 2.5% last month.

The last of the large developed economies are Europe and Japan. Both of their respective Central Banks have recently adopted negative interest rates in a desperate attempt to fuel inflation and spur economic growth. Whether their monetary policy achieves the desired result remains to be seen. However, expecting a resurgence in economic growth to fuel commodity demand from these two regions is hopeful at best. Lastly, let’s look at emerging markets. Unfortunately, the majority are stuck in low to negative growth as a result of a collapse in commodity prices. Taking a broader view of the World, there are few, if any, bright spots. Using this macro view of the world economy, it should bear no surprises that stockpiles of oil have been building up to levels not seen by many of us in our lifetime.

As you start to put the pieces of the puzzle together, the prospect of a sustained recovery in oil prices seems limited. While supply cuts or freezes may help, the key driver for oil and commodity prices in general, will be a resurrection in global economic growth. In the long run, there is no doubt that there will be great buying opportunities within the oil and gas sector. In the short run, however, there may be a lot more pain.