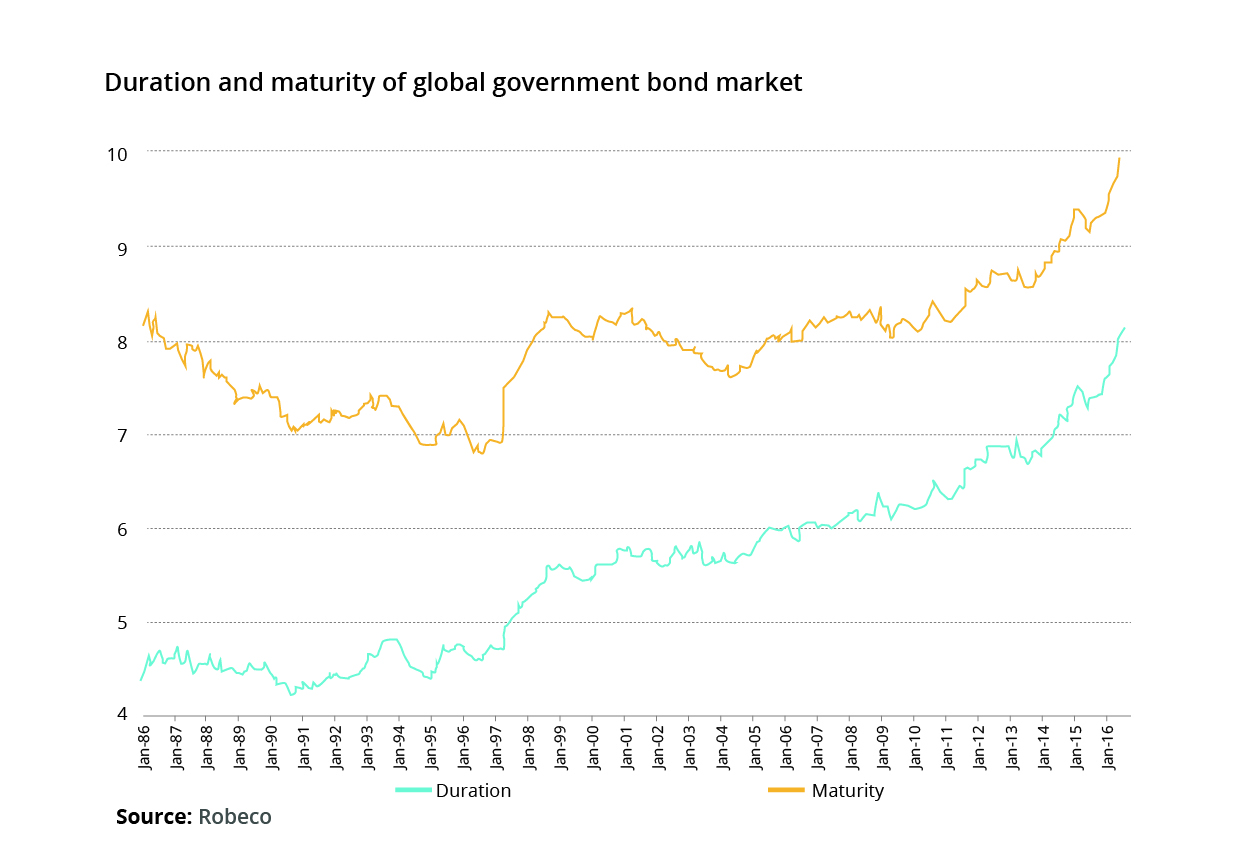

Over the years, the average duration of fixed income indices globally has grown steadily, gathering pace over the past decade. Durations of sovereign bond indices globally doubled from 4.3 years to 8.1 years in 30 years leading up to June 2016. They grew on average from 6 years to 8.1 years in the last two years, with more than half of that increase seen in the last two years, according to Robeco Institutional Asset Management.

Duration of emerging market bonds has risen steadily for decades, too. According to JP Morgan analysts, the main driver behind rising duration of fixed-income indices is the continuing low-yield environment in developed markets, which is forcing investors to turn to emerging markets. This in turn allowed yields across emerging market assets to come down enough for countries to try and lock in these rates for longer maturities.

“It does make sense for high grade issuers to go long, particularly those wanting to appeal to Asia investors that look to bridge the gap between assets and liabilities,” said Zeina Rizk, Director of Fixed Income Asset Management at Arqaam Capital. “With tranches at 30-year tenors the curve is flat, so it makes sense to extend to thirty plus years.”

“It does make sense for high grade issuers to go long, particularly those wanting to appeal to Asia investors that look to bridge the gap between assets and liabilities,” said Zeina Rizk, Director of Fixed Income Asset Management at Arqaam Capital. “With tranches at 30-year tenors the curve is flat, so it makes sense to extend to thirty plus years.”

“Looking at Brazil, for example, even compared to last year there is a significant fundamental improvement, even the ratings outlook was moved negative to stable by Moody’s. And with stability in the oil market, there is a feeling that the fundamentals have bottomed out so the outlook is positive and longer tenors are becoming more appealing. But this could change very quickly,” Rizk admitted, pointing to US monetary policy as one of the big risk factors.

The upward pressure from the Fed’s hiking cycle is certainly pushing some EM sovereigns to tap the markets while rates are still relatively attractive.

Brazil, for example, took the opportunity to issue a US$1bn 10-year 5% bond, which last year carried a 6% yield. On the corporate side, Suzano recently broke new ground by selling a 30-year US$300mn note, with a Treasury spread of around 433bp or some 140bp over its existing 2026s, which are trading at a G-spread of 293bp.

Some sovereign issuers that have been averse to longer maturities in the past are now easing regulations to help push tenors out on new issuances: Kuwait is currently preparing a draft law to allow maturities of up to 30 years. Both Saudi Arabia and Oman had included 30-year tranches in their recent sovereign Eurobonds.

Push-and-Pull Factors

Sergey Dergachev, Senior Portfolio Manager and Lead Manager for Union Investment Privatfonds, identified three major factors behind this rise in 30+ year tranches across the EM space.

First, according to the expert, there is a generally better perception of EM debt in terms of credit risk.

“Twenty years ago, an issuance of a ten-year government bond was exotic; the fact that nowadays sovereigns and corporates can issue thirty-year debt signals that investors have faith and positively view credit fundamentals improvement in EMD over recent years.”

“Secondly, there is growing demand for pension asset management within EMs, investors are looking for ‘long money’, and even insurers in the developed world look for attractive investment destinations that offer juicy yield pick-up with manageable risk versus exposure in developed markets debt.”

Finally, Dergachev pointed to the recent general trend of EM sovereigns and EM corporates looking to diversify their funding and maturity profile by extending the average tenors on their allocations.

Another factor in play, as always, is the Fed’s monetary policy outlook: the well-anticipated rate hike in March coupled with a generally dovish tone struck by the Federal Reserve meant Treasury yields actually came down slightly, with 10-year notes shedding 3bp to 2.472%, with the yield on the 30-year bond shedding 2.4bp to 3.088%.

That is boding well for emerging markets, particularly given previous concerns around the impact of the new US administration on market sentiment and valuations – the so-called “Trump Effect”.

“I think that EM is showing signs of recovery following Trump’s election, a lot of his policies are softening, and getting pushback from regulators, which helps ease fears that dominated the EM space during the election,” noted John Peta, Head of Emerging Market Debt at Old Mutual Global Investors.

The administration also seems to be striking an EM-positive tone; US Trade Secretary Peter Navarro hinted in March that the US, Mexico and Canada could form a manufacturing powerhouse together.

“After Trump’s election, observers had strong reflationary expectations and 30-years Treasuries sold off quite a bit on high inflation expectations. This perfect storm for EMs has largely dissipated by now and the damage is not as bad as some feared. Volatility has calmed down, risk assets around the world – equities and bonds – continue to perform pretty well, EM liked that rally and is catching up, offering decent yields,” Peta concluded.

The growth in savings and development of financial markets coupled with slimming current account deficits being and stabilising currencies in some of the larger emerging economies have proven extremely beneficial. And, with an estimated 30% of global government debt now offering yields of less than zero, there is a combination of push-and-pull factors encouraging global asset managers to continue betting on markets they would have considered too risky in the past.

“Benchmarked index investors also like thirty-year tranches, since those are part of EMBI and CEMBI indices, in most cases. US real money accounts do like thirty-year deals out of Asia, LatAm and MENA. Usually, demand from local real money accounts for ultra-long end has been relatively low, and, ironically, it mostly concentrates around front-end and intermediate maturity bucket of the curve.”

The analyst pointed to Metro Santiago’s recent 30-year issuance as an example of generous pricing and stellar secondary market performance, which, he believes, stemmed from a relative scarcity today of these kind of tenors, particularly in secondary markets

Other analysts, though, are less convinced that there are any fundamental improvements in EM debt that are behind this emergence of longer maturities.

John Peta, for one, did not see any significant change in quality of EM credit; instead, the rising popularity is coming from the traditional investors, such as global insurers that have been involved in emerging markets for over a decade now, being more comfortable with taking on longer durations.

Echoes of 1994

Some have warned of the risks inherent in such assets – even if they are, for now, less urgent than they were five or ten years ago. A sudden interest rate hike would make 30-year bond prices extremely volatile. And with a large share owned by insurers and buy-and-hold investors, these kinds of instruments tend to be more “sticky”, with liquidity often evaporating within one to three weeks after the issuance.

With that in mind, how sustainable this rise in popularity of long-duration debt will depend on two factors. One is the general supply of 30+ year debt, which is more likely to be found kicking around Latin America more than other regions like MENA or Asia. The second factor is general demand for longer term money, driven by growth in EM pension assets, and the yield environment in developed world.

Peta, meanwhile, takes a more pragmatic look at the market, warning that any trends of asset diversification – including by betting on longer debt – could be undermined by a possible end of the 30-year-long global bond rally, which could be triggered by sudden movements by the Fed.

“Certainly, the Fed remains a concern. Wage inflation in the US has been creeping up, and while recent figures have been lower than feared, if that trend continues, it would put pressure on the inflation outlook and, consequently, on long-term bonds.”

“It is worth being wary of a potential repeat of 1994, where the US 30-year yield jumped more than 150bp to 7.75% after a rate hike, as it started to tighten policy following recovery from the 1991 recession,” Peta warned, adding that this scenario remains on the hawkish end.

So far the Fed has been very cautious and transparent in its tightening, signalling any moves from afar and giving the markets time to adjust and price them in. In these circumstances, it may not be the Fed that triggers the slowdown, but instead the “wildcard” of global politics – Donald Trump.

“For both the buy side and the sell side at the moment it is all about timing and duration,” Rizk explained. “But then again, much depends on the Fed rate trajectory – if Trump were to announce a massive fiscal plan tomorrow, then the curve will blow up and it will become more expensive to issue longer maturities”.

All in all, it appears that longer-duration debt in emerging markets is gradually becoming part of the mainstream for issuers and investors; the appealing low-rate environment, for now, will encourage more supply to come to market. Sudden jumps in global rates would certainly act to undermine that trend – but, were such a factor to come into play – price volatility in long-term bonds might end up at the bottom of the list of concerns for global debt capital market players.