The East African economy’s sound macroeconomic management and fiscal discipline over the past decade and a half has seen it grow at an impressive 7% real average rate per annum, with the recovery following the country’s tumultuous civil war in the 1990s largely driven by wholesale and retail trade, as well as sectors like construction, tourism and agriculture, exemplifying the success of the government’s diversification efforts.

The East African economy’s sound macroeconomic management and fiscal discipline over the past decade and a half has seen it grow at an impressive 7% real average rate per annum, with the recovery following the country’s tumultuous civil war in the 1990s largely driven by wholesale and retail trade, as well as sectors like construction, tourism and agriculture, exemplifying the success of the government’s diversification efforts.

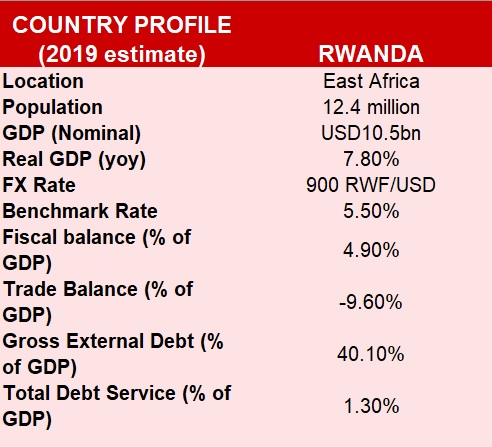

The economy is forecast to grow 7.8% in 2019, according to the National Bank of Rwanda’s official forecasts, with inflation hovering around the 3% mark. Authors of a Renaissance Capital report on Sub-Saharan Africa note that Rwanda is a well-managed economy that promises “strong supply-side driven growth, low inflation and a sustainable fiscal position over the medium term.”

Rwanda – Contribution to Real GDP Growth, %

East Africa’s Economic (R)Wonder

East Africa’s Economic (R)Wonder

Rwanda’s outstanding performance in recent years has not gone unnoticed, with EFG Hermes listing the country among the top-10 investment destinations in the EM space in 2019. How did such a small and seemingly insignificant – from a global investor’s perspective – nation achieve this? In a tragically ironic sense, the country’s troubled past – and its conscious decision to break with it by becoming more open and transparent – held the key to its spectacular progress.

“Rwanda is a model fast growing economy in East Africa, whose economic transformation is premised on its visionary leadership’s commitment to good governance and services above its own interests,” Peter Mathuki, Executive Director of East African Business Council says. “After the Civil War ended, the Rwandans took it as a lesson and decided to never again go down that route. Instead, they focussed on opening up the economy, developing industries like services and tourism, anchored by strong governance and anti-corruption frameworks.”

With good governance, strong institutions and the rule of law well established, the business environment has flourished as the country shot up in the Ease of Doing Business rankings, pushing into 29th spot among 190 economies (second in Africa after Mauritius) according to the latest World Bank annual ratings, from 41 in 2017. Foreign direct investment has risen steadily from USD223mn in 2015 to USD293mn in 2017, and Renaissance Capital expects it to reach USD500mn this year, representing 4.4.% share of GDP (up from 2.7% last year).

Rwanda – Ease of Doing Business Rating

As Christopher Marks, Managing Director, Head of Emerging Markets, EMEA at MUFG points out, the East African country was inspired by the Singaporean model, turning its weaknesses – small size and relatively remote location – into strengths.

As Christopher Marks, Managing Director, Head of Emerging Markets, EMEA at MUFG points out, the East African country was inspired by the Singaporean model, turning its weaknesses – small size and relatively remote location – into strengths.

“[Rwandans] also want to become a hub of commerce and finance in the region, with strong institutions and high levels of transparency,” Marks explains.

According to the Rwanda Development Board, a government institution tasked with promoting investment opportunities in the country, there are a number of factors that make the country an attractive destination for international capital, including sustained high growth rates, robust governance and access to a market totalling 10mn people, a figure that could expand significantly as the integration of EAC economies intensifies.

It also references a liberal trade regime, which includes certain perks for members of the EAC including duty-free access to the EU and American markets, as well as a bilateral trade agreement with South Korea and double taxation agreements with the likes of South Africa and haven economies such as Jersey.

Finally, it offers more specific incentives, both fiscal and non-fiscal, for investors looking to gain exposure to its “priority sectors”. These include zero corporate income tax for companies willing to relocate to Rwanda, 15% preferential corporate income tax for strategic sectors like energy and ICT, exemptions of capital gains tax and repatriation of capital and assets. Non-fiscal benefits include reduced red tape on business registration, government assistance with tax-related services and exemptions, in securing access to utilities and with obtaining visas or work permits.

“They are reaping the benefits of EAC integration and improving trade area, and hold a competitive edge due to some of these investment incentives. Notably, the US commodities exchange is operating out of Kigali because of its institutional strengths, providing information on auctions of grains, soybean and other commodities; and being surrounded by distressed countries like the DRC and Burundi also puts Rwanda in a good light,” Marks noted.

Fiscal Limitations

Nevertheless, Rwanda is still a very small economy, in many ways incomparable with the regional powerhouse that is Kenya, or even the smaller Ethiopia and Tanzania – the IMF anticipates its size reaching USD12.8bn by 2022. That is significant because the market should not forget to keep bottom-up forecasts within top-down realities that determine the system’s scalability, according to the EFG Hermes report.

“Scale is very important,” says Muammar Ismaily, EFG Hermes banking sector analyst. “A USD9bn economy with a small and underbanked population cannot support a large market, and until that changes the retail segment in the economy will remain small.”

The disconnect between expectations and reality is particularly pertinent when assessing the East African economy’s budget balance and creeping indebtedness. As for many frontier economies in transition, bringing down the fiscal deficit has been a constant struggle: after breaking even in 2008, the deficit widened to -5.4% of GDP in total by 2015, before paring back to -3.2% in 2016, according to TradingEconomics data.

Renaissance Capital, analysing figures from the IMF and World Bank, expect the budget deficit to widen in FY18/19 (July-June) on the back of higher investment spending. The budget deficit (including grants, cash basis) is set to increase to 5.4% of GDP in FY18/19, from 4.9% in FY17/18, to accommodate higher investment spending, which will be financed through concessional loans.

Notably, over the past two years the IMF had to revise down its forecasts on the fiscal side. Likewise, current account figures are lagging behind estimates: the deficit last year narrowed to -14.1% from all-time high of -16.6 in 2017. The current account deficit is indeed very high, but there are some silver linings.

“They are making some progress by increasing export volumes as the currency remains stable; they also maintained high growth momentum for past 2 decades, up until 2016, when a tough 2-year period occurred mainly due to external factors – in this case, drought,” Ismaily says.

“They are making some progress by increasing export volumes as the currency remains stable; they also maintained high growth momentum for past 2 decades, up until 2016, when a tough 2-year period occurred mainly due to external factors – in this case, drought,” Ismaily says.

Debt Sustainability

The country’s debt stock is the trickiest part of the fiscal equation. Government debt to GDP remained steady at near 20% until 2013, when it began to rise at pace and reached 40.2% in 2017. According to Statista, projections for the next three years, that number is expected to hit a peak of 43.4% this year before beginning to edge down.

Rwanda actually has the lowest debt burden in East Africa, and the debt servicing costs’ portion of GDP has been kept below 2%, which is projected to fall in the coming years.

This is in part due to the sovereign’s successful foray into international markets, when it issued a USD400mn Eurobond that saw nearly 8x oversubscription and provided the funding base for its development initiatives, including financing of the USD150mn Kigali Convention Centre costs and USD80m for RwandAir, as well as debt restructuring.

“With the narrative of raising money for the conference centre and RwandaAir, they placed a significant USD400mn issuance at a coupon of 6.63%, which traded above par. It came on the back of efforts in the preceding decade that reduced debt levels enough to secure affordable pricing,” says Greg Smith, PhD, Fixed Income Specialist, Renaissance Capital.

“With the narrative of raising money for the conference centre and RwandaAir, they placed a significant USD400mn issuance at a coupon of 6.63%, which traded above par. It came on the back of efforts in the preceding decade that reduced debt levels enough to secure affordable pricing,” says Greg Smith, PhD, Fixed Income Specialist, Renaissance Capital.

And the 2013 Eurobond was remarkable not just because of its size relative to the economy, says Marks.

“The oversubscription, which reportedly reached 10x at peak, was impressive. They could have upsized significantly with this level of demand, but they were frugal and borrowed no more than was necessary – an admirable act of discipline. And the convention centre it funded is already paying for itself: it has boosted the tourism and conference industries, as well as improving air transport, which in turn allowed to capture higher value tourism like business travel,” notes the MUFG banker.

Shift to Local Markets

Despite the success of the 2013 issue and a spate of high-yield peers tapping international markets in recent times (including first-time issuers like Uzbekistan, Benin and Belarus), few expect Rwanda to come back to the Eurobond market this year. This is partly a reflection on its prudence – only issuing when there is a specific requirement for the proceeds, such as a large construction project; and partly it reflects a shift towards the domestic markets.

“The 2013 issue was used to finance the new airport and convention centre, but since then they have been moving towards bilateral types of borrowing or syndicated loans via big local banks to infrastructure developers and construction firms, with some exposure passed onto foreign banks operating in Rwanda. Local banks thus pick up the bulk of the financing requirements and are in turn funded by customer deposits in a liability-side driven model, along with DFIs,” Ismaily says.

One recent example of the latter was an agreement signed in September 2018 with Nordic Investment Bank (NIB) and the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), setting up a 10-year loan programme for Rwanda worth EUR100mn. The proceeds are expected to go towards financing projects within infrastructure, such as energy, telecoms, industrial parks and special economic zones, roads, railways and harbours.

Attempts to foster and expand the domestic markets have been hit and miss so far. In 2017, the country’s Capital Markets Authority insisted that doing so will facilitate financial intermediation and domestic savings mobilization, while reducing dependence on foreign aid and hard currency borrowing.

Attempts to foster and expand the domestic markets have been hit and miss so far. In 2017, the country’s Capital Markets Authority insisted that doing so will facilitate financial intermediation and domestic savings mobilization, while reducing dependence on foreign aid and hard currency borrowing.

In practice, however, with low levels of turnover and limited liquidity, that deepening has not yet materialized; aid flows have been stemmed somewhat, and the domestic debt’s share of the budget has crept up. IMF data shows that Rwanda’s domestic debt has almost tripled from USD300mn (5% of GDP) in 2010 to USD850mn (10% of GDP) in 2017, and – with low deposit rates – this trend threatens to become unsustainable. As external obligations continued to rise alongside domestic debt, the WorldBank warned that “Rwanda has been unable to maintain its spending amidst aid decline.”

This is especially problematic in a place like Rwanda, where the banking sector is quite consolidated.

This is especially problematic in a place like Rwanda, where the banking sector is quite consolidated.

“The Bank of Kigali is by far the biggest in Rwanda, holding 38% of the market share and 80% of loans in corporate segment. It is a high growth, low penetration story, but developing retail banking is challenging, in large part due to national identification system challenges: for example, credit assessment bureaus are still rare here,” one banker operating in the country observed.

The government is pushing through initiatives aimed at bolstering the domestic markets and reaching 90% financial-inclusion rate by 2020; only 26% of Rwanda’s estimated 6 million adults were banked, according to a 2016 survey by FinScope.

The Central Bank in December 2018 has begun gradual implementation of the Basel II regulations, recapitalizing and raising capital ratio requirements on local banks, from RWF5bn to RWF20bn (and RWF50bn for development banks). It also shifted to a price-based monetary policy framework (from monetary-targeting regime), so as to aid the development of money markets.

The reforms are already having an impact: the Bank of Kigali recently launched investment and insurance arms of its business, which position it to lead the way and incentivize other large lenders to follow suit.

Additional, innovative and fintech-based solutions are also being discussed, with microfinance institutions playing a growing role in supporting East African economies; integration between banks and telecoms has enabled sustained growth of financial inclusion rates in Kenya, and the likes of Rwanda are slowly catching up. Tighter integration and increasing connectivity are for now the key priorities, multiple experts suggest.

“Rwanda just finalized another IMF programme, have some bilateral debts outstanding, but debt accumulation remains relatively prudent. With capital markets still nascent, the solution is tighter integration with neighbouring economies rather than deepening domestic market,” Smith explains.

Looking for Projects

In the longer run, the government is still looking to shift some of its risk and financing duties onto the private sector. According to Afamefuna Umeh, Executive Director, Head of Sub-Saharan Africa Fixed Income Sales for Exotix Capital, public investments have been the main driver of growth – including successful co-financing initiatives – but some practical constraints remain, including the low domestic savings rates and high costs of energy, as well as a large skills gap.

“The slowdown of 2016 exposed the limitations of the public sector-driven model. Promoting savings and reducing poverty (from 44% in 2011 to 39% in 2014 and falling, as cited by the world bank report on Rwanda) now ought to encourage private sector activity and boost direct capital inflows. Privatization and targeted subsidies can be used to reduce costs of energy,” Umeh says.

In Rwanda, corporate borrowers are too often overshadowed by the sovereign, so private placements and other mechanisms – including PPPs and project financings, most involving some level of development bank participation – could be the answer.

“PPPs are becoming a significant instrument – some of the recent projects are shared-risk developments, often skewed towards Asian partners – especially China,” Umeh points out.

According to the Rwandan Development Council, investments in the country reached USD2bn in 2018, a reported increase of 20% year-on-year, spanning 173 projects – a stunning achievement for a USD9bn economy.

“They are beneficiaries of a lot of development money, in the energy space for example; telecoms have been harder to bring in due to geographic idiosyncrasies, but still they have come up with some interesting solutions,” Marks says.

One of the more impressive cases saw the government agree a USD400mn concession with private developer Gasmeth Energy to extract methane from under Lake Kivu, which reportedly contains enough reserves to power the country for 50 years. Gasmeth Energy, which joined the likes of Contour Global and Symbion Power in tapping the lake’s potential, has agreed to finance, build and maintain a gas extraction and processing plant, to sell it on domestically and abroad.

Among other examples is a landmark USD350mn 80-MgW peat-to-power project in the Gisagara District – arranged by AFC as a project financing, with total senior debt facilities of USD245mn, contributing USD75mn in loans and providing an underwriting commitment of USD35mn million. Finnfund, a Finnish Development Finance Company, served as the lead arranger for total mezzanine debt facilities of USD35mn, in participation with TDB, Afreximbank, Export-Import Bank of India, and Rwanda Development Bank (BRD). Notably, the project was sponsored by Hakan Madencilik A.S – an energy company from Turkey, and Quantum Power, a power and energy infrastructure investment platform.

“As evidenced by some of the recent transactions, a queue of global organizations is there, ready to step-in and provide expertise or funding of the grid projects,” Gregory Smith adds.

Kagame Over? Not so Fast!

As with any young and fast-growing emerging economy, there are numerous risks that can undermine or undo years of progress. Political risk is less prominent in Rwanda than many other African countries, but it could rise. Paul Kagame is heading into his third decade as president; having taken office in 2000, he was elected following a constitutional amendment in 2003, won elections in 2010 and 2017, and – still only 62 – could well stay in power into the 2030s.

Despite his relatively “clean” record, it is not unknown for long-time leaders to consolidate power with repression or by seeking out external enemies.

“It is worth pointing out that any head of state in power for 15+ years is a potential liability; and it’s a tough neighbourhood. Current tensions on the Uganda border are a warning sign. But tightening the EAC community should alleviate some of those threats,” a banker who preferred to remain anonymous tells Bonds & Loans.

Mathuki, in turn, says that as Rwanda is landlocked with no open access to sea, its dependence on good relations with its seaside neighbours could set policy priorities to a great extent.

“They cannot control internal problems in those countries, but need to minimize frictions, as investors need to have a sense of security,” Mathuki stated.

Factors that have for years appealed to investors – political security and “running a tight ship” – could thus eventually turn into a deterrent. Rwanda risks going the way of Tanzania, where state protectionism has significantly dented investor appetite. And international sanctions could also come into play, particularly if there are more reports of the ruling government persecuting opposition leaders.

On the economic front, high levels of poverty, low literacy levels and poor electricity generation – with half the country still off grid – remain the biggest weaknesses impeding its path to industrialization. Expanding communication networks and the electricity grid to remote communities is a top priority, but progress could be slowed by external risks, such as natural disasters or famines, which the government could struggle to deal with.

For the foreseeable future Kenya will naturally retain its pre-eminence in the East African Community due to its sheer size, while Rwanda will continue to put emphasis on processing and high value-added production domestically.

“But it will continue to stake out its turf in the global markets and production chains, even if the scale remains limited – more niche and higher value,” Marks concludes.