Anomaly. Ridiculous. Pure madness. These are just some of the terms market observers are reaching for to describe the international debt market following the Fed and other Central Banks’ reversion to monetary easing earlier this year. As developed market investors grapple with flat or negative interest rates, their emerging and frontier market peers are piling into high-yield bonds. Exotic or debut issuers are having a ball – but how long will the party last? To a large extent, it depends on how you look at the link between fundamental and technical factors at the heart of investment decision-making.

In a telling anecdote from 2017, when Tajikistan, an obscure Central Asian Credit by most measures, sold its inaugural USD500mn Eurobond to fund the construction of the Roghun dam, over 300 global fund and asset manager accounts piled into the notes. The deal was 9x oversubscribed at peak.

“It was madness, the largest book in my professional career (by number of participating accounts), including all the ‘usual suspects’ – investors that you will on average find on most benchmark bond issuances,” said a DCM banker who worked on the deal.

Two years on – and one half-hearted rate-hiking cycle later – we are back to square one. Negative yielding asset volumes recently shot past the USD15tn mark, while exotic sovereign credits like Benin, Ghana, Sri Lanka, El Salvador, Ecuador and Uzbekistan hit the Eurobond markets as borrowing costs dropped to record lows, ranging from 9% to as narrow as 4.75%.

Sovereign Eurobond Issuers 2017-2019

“Flows have been pretty strong into EM from the beginning of the year, which encourages investors to look into higher yielding names to diversify their portfolios, but to also new issuer premiums,” explains Kaan Nazli, Senior Economist and Portfolio Manager at Neuberger Berman.

“May to year-end 2018, as global rates looked to start rising, was a pretty poor period for EM and FM debt; that may happen again in autumn 2019, but so far we are seeing crazy demand for anything over 6%,” says Alexander Bulgakov, Executive Director, Debt Capital Markets at Raiffeisen Bank.

With all due respect to Tajikistan and Benin, they are hardly the kinds of safe havens for global investors that the current yields seem to indicate. The reasons for this include a complex combination of economic and structural – mostly external – factors that are driving the latest hunt for yield.

“Some of the credits have a headline risk premium on them, but that tends to be temporary,” says Stuart Culverhouse, Chief Economist at Tellimer. “Ratings are another factor… in this frontier territory you are likely single B-ish and the typical yield is 7-8% - it’s the new 10% seen a few years ago, or 12% a few years earlier. But then you have the likes of Uzbekistan, a BB, slightly higher grade but still a new issuer – and they came at around 5%.”

But the question increasingly being asked of investors and asset managers is this: has the natural balance between fundamentals and technicals, as determinants of bond prices at least, been increasingly upended in favour of the latter?

Low Bar, High Potential

Before delving into the technicals, it is worth pointing out that the underlying stories of some of the most underdeveloped and peripheral markets across the global investment landscape offer much promise, particularly for investors that come into those credits for the long-haul. Low penetration of goods and services in these economies in a globalized world means GDP growth estimates are among the highest in the world for these countries for the next five years – particularly for several of the most populous better-known frontier nations like Pakistan and Nigeria, and others, such as Myanmar and Sri Lanka, which have emerged from decades of relative obscurity.

These are supported by favourable demographics, rapid urbanisation, technology transfer and abundance of private credit. These factors tie into another structural improvement that was too slow to take hold and hard to assess in the past: that is, stronger governance, accountability and rising transparency, often driven by international investors and development banks’ conditions and demands.

As investment destinations, these credits offer convergence and diversification opportunities as they open up to FDI flows and adopt international best practices.

“Correlations relative to developed markets have generally been lower than their emerging markets peers, as have intra-country correlations within frontier markets itself given the highly diverse nature of the asset class,” Aberdeen Standard Investments notes in a recent research paper.

With a lack of relevant benchmarks in the market, pricing such issuances can be tricky, which creates an opening for more experienced and involved investors to capitalize on market inefficiencies, often caused by headline risk, poor press and research coverage or short-term liquidity squeezes. The more exotic trades typically see less participation – and therefore less competition – from other market players, which adds to their appeal.

“It helps if you have a positive story to tell,” Culverhouse explains. “We have seen debuts from different rating categories, which is also a factor in the level of demand. Often it is hard to judge pricing on those benchmark-setting Eurobonds because it is in a sense counterfactual: we’ve seen pricing below targets, but then again it could be that those targets were elevated to boost demand in the first place.”

This is particularly acute when assessing debut issuances through comparisons with similar credits. Benin and Ghana are examples where the latter was compared to the former but saw a new issue premium on top, even as the countries are similar in terms of macro outlook and revenue flows.

As Joe Delvaux, CIO Global Fixed Income at Duet Asset Management, points out, sometimes the allocations are extremely low and therefore relatively insignificant to global funds, which means they can focus strictly on the numbers and not the underlying economies.

“Unfortunately, often people only start paying attention to fundamentals and researching when the downturn has already hit… It’s like buying a hose when the house is already on fire,” he muses.

Record Low Defaults

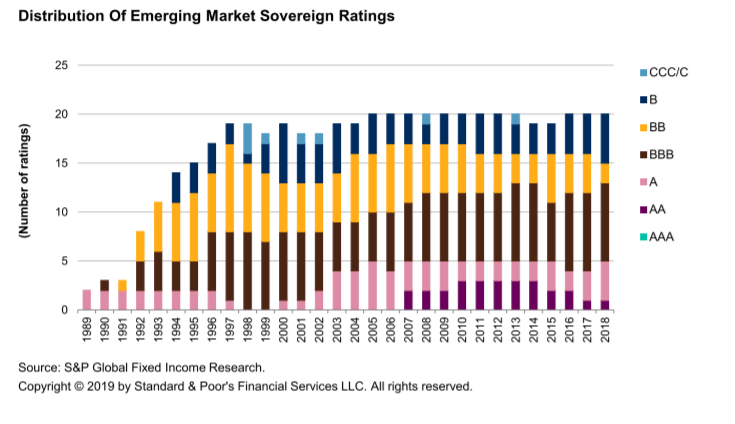

One supportive factor is the effective disappearance of sovereign default cases from the international markets, and a broader improvement in credit quality worldwide. According to S&P, as of 2018, number of credits rated B or lower increased slightly compared to the previous 15 years, but remained below 6, while BBB or higher rated credits has risen steadily over the past 30 years and peaked at 13 last year.

Bulgakov is convinced that the vast demand the sovereign high yield issues are gathering is down to the external conditions rather than their idiosyncratic stories.

“Just look at the latest global default rates, they are minimal. The risk of default on a given credit is less of a threat than a fall in profits for a given portfolio due to low average yields.”

In this environment, high yielding Eurobonds from frontier markets that offer highest returns on the market as well as near and medium-term political stability, like Central Asian republics or GCC countries like Bahrain, seem to be garnering high levels of demand. But, as Edwin Gutierrez, Portfolio Manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments warns, that does not absolve investors from due diligence when exploring a country’s fundamentals.

“They aren’t ‘no-lose’ bets,” he notes. “The likes of Tajikistan or Suriname have thrived in this environment, and while neither has defaulted, they have also been laggards. Suriname was briefly in profit, but for much of the bond’s lifetime it has been under water. Defaults are low in the asset class in general, but understandably its higher in frontier markets, because they have higher debt to GDP ratios and higher interest costs, so it is important to consider those aspects.”

And while a broad rise in ratings is a tailwind, so are factors like the trajectory of fundamentals or the policy outlook, especially for countries that don’t have a credit history or a track record, and only managed to get a foothold on the international markets due to the abundance of cheap credit.

“They have to stay disciplined and maintain sound policies, otherwise their borrowing costs start to rise,” warns Culverhouse.

Free (Money) For All

A return to easing among global central banks, at a time when interest rates in most developed countries are already at record lows, has provided by far the biggest boost of adrenaline for emerging and frontier issuers.

“The fundamentals of the countries issuing debt of course vary on a case by case basis. But the decline in EM dollar yields you tend to see when Treasury yields fall tends to be broad based,” William Jackson, Chief EM Economist at Capital Economics, concludes.

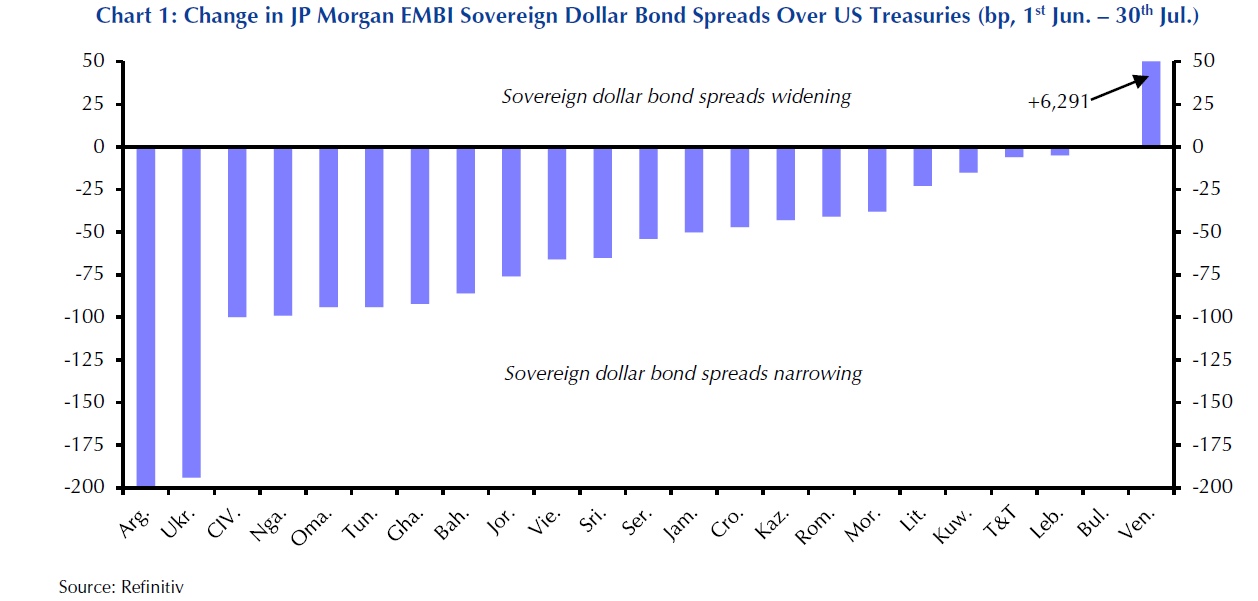

Sovereign dollar-bond spreads have rallied across frontier markets, according to Capital Economics data, by a wider margin than in other parts of the emerging world. Barring Venezuela, frontier market dollar bond spreads over US Treasuries narrowed by an average of 30bp – the broader EMBI index has narrowed by a modest 9bp, with bonds from the Gulf (particularly Bahrain and Oman), Argentina, and Ukraine outperforming the rest (until Argentina’s recent political setback).

“You can argue that positioning has been stretched in a lot of risk assets, though it is not specific to emerging markets. Naturally you are seeing these inaugural issuers coming out to take advantage of relatively low borrowing costs – they aren’t stupid,” says Gutierrez.

That is not to say that everyone is getting the deal of a lifetime. Even in favourable environments, timing is crucial; in some situations, it becomes more important than the issuer’s fundamentals.

“Timing could make a difference of 100-200bp these days and becomes in itself a psychological factor. But as an investor, you are interested in catching out the “badly timed” deals, because you don’t want to leave extra money on the table”, notes Miguel Zielonka, CFA, EconViews.

A recent deal in the Republic of Georgia illuminates this well, where a telecoms company was persuaded by one of the deal’s arrangers, a leading American investment bank, to tap the market at 11%. The price soon dropped into single digits on secondary trading, suggesting the issuer overpaid almost 200bp.

Mongolia’s two Eurobonds are a telling case in the sovereign space: both benchmark-sized (USD500mn and USD800mn), 5-year and 5.5-year tenors, the second issuance came in 2017, just a year and a half on from the first, and priced at 5.625%, more than 500bp tighter – even after a ratings downgrade. Another sovereign, Togo, is rumoured to be planning a debut foray into the international markets, and the prospects of 11% yield already have investors salivating, according to one fund manager who spoke to Bonds & Loans.

There are, naturally, numerous reasons for economies with very nascent capital markets to tap the Eurobond markets. Some are going through a tough period and require support, especially if they are part of an IMF stabilisation programme. Ukraine is one such case.

Others are countries that have reached the stage of development where they want to build a sovereign curve, potentially opening the market for domestic companies, and to enhance their appeal through the transparency, disclosure and engagement implied through the bond issuance process.

“Uzbekistan fits into the latter category,” says Nazli. “It has substantial reserves and it receives a lot of financing from international financial institutions, which is cheaper than financing from the market. Neuberger Berman were involved in this issue. We didn’t buy any of Benin’s issuance, on the other hand, though mostly due to the fact we’d reached our limits on exposure to the region, and not necessarily to do with the credit itself.”

Others are able to “piggyback” on the support of a strong regional powerhouse or “patronage” due to historic links. Examples of this may include Bahrain, benefiting from close ties with KSA and UAE, while its own credit quality is arguably quite weak, relatively speaking. In Europe, countries like Ukraine or Serbia are seeing borrowing costs plummet as they line up to join the EU. Central Asian Republics and former CIS states are closely intertwined with the Russian economy.

“There are talks that Armenia might be coming to market in the near term, and Belarus could potentially do a follow up issuance next year. These are seen as proxy credits for Russia that provide exposure to the rouble without the sanctions risk attached to the Russian sovereign and state corporates,” explains Bulgakov.

In Africa there are similar “historic” ties between the likes of Tunisia and France, whereby French investors would dominate the books of such issuances, and that also leads to some sovereigns to issue in Euros. But the continent is also quite unique from that perspective.

“It is less of a “proxy” than those other cases. In part it is because of entirely different scales of support: a mere USD1bn could help revive the economies of Republic of Congo and Gabon, while a Ukraine or a Greece would need tens of billions,” Delvaux says.

The EUR-denominated market is also quite different in terms of the investor make up. While it is monitored by global asset managers, the main buyers tend to be European pension funds and insurance companies. In these cases, the success of an issue is more conditional on the quality of the specific issuer’s credit, rather than broader macro conditions or regional outlook.

Indices and Allocations

One factor that differentiates USD and EUR bonds is how they are indexed. Most US dollar-denominated notes end up in the JP EMBI, which enjoys higher market capitalisation than its EUR-denominated comparables. This highlights one of the most important drivers of demand for EM and FM markets in recent years: whether and how they are indexed.

As more and more exotic credits are picked up by mainstream indices, they increasingly end up in the portfolios of so-called “cross-over investors”, or tourist investors that do not necessarily have deep insight into an obscure credit’s idiosyncrasies.

Some credits see a rise in scarcity value, when fund managers have to allocate a certain amount of capital to a given region which hasn’t seen a lot of issuance. The issuance amount and liquidity available determine on whether the bond is included in an index, and not all bonds are included into ETFs. The downside of this, some argue, is that there is a real danger that a wobble in the market could lead to mass outflows.

“Sometimes large global investors take up 50% or more of a given sovereign issuance allocation – when these are not completely natural positions for them to hold. In the frontier markets, cash appreciation and yield compression is highest in this asset class. And while developed EMs have local institutions bidding on these notes, allowing them to absorb a sell-off, there usually aren’t any in FMs, which means price gaps tend to be substantial and they get oversold quickly,” Delvaux says.

Culverhouse counters that as most of the FM issues end up in an index – given they are benchmark-sized - if they end up in a standard EM bond index, they will fall into the portfolios of most mainstream EM fixed-income investors, so they are not segregated in a separate “frontier” section.

“There are few dedicated fixed income frontier funds, so these investors aren’t really crossing over. But of course, in ETFs or retail space, investors may not be as familiar with these more obscure names.”

He concedes that the presence of some cross-overs could potentially make the individual bonds more susceptible to flight, mostly due to the fact that they are generally more sensitive to headline news than frontier market “veterans”.

“But some of these bonds aren’t very liquid, so ironically, the more mainstream notes would probably be sold off first,” the investor concludes.

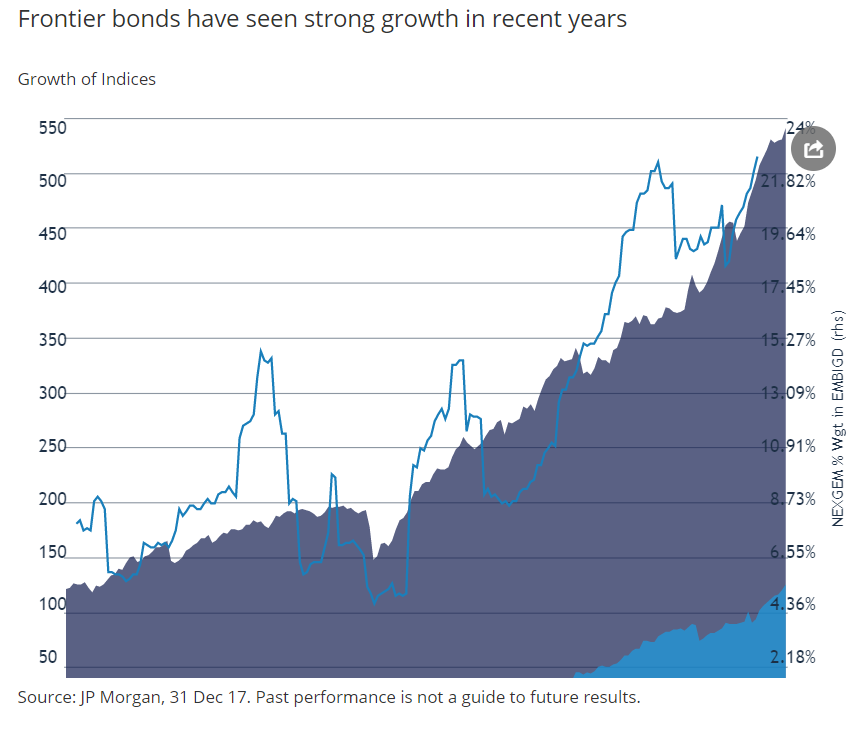

While most of the frontier bonds do indeed end up in standard EM indices, dedicated frontier indices like JP Morgan’s NEXGEM are gaining traction. The weight of NEXGEM countries in the EMBI GD has increased to 24% as of 2018. True, real money investors can on some occasions raise cash, says Gutierrez, but the fact of the matter is that they are being paid to manage other peoples’ money, which means they have to stay invested in order to help guarantee a hefty return in the long-haul.

“When you have a high portion of a portfolio in cash, that erodes some of the return.”

For now, while EM yields are depressed globally, spreads are still tangible, compared to DMs. This raises important – and worrying – questions for those investors whose exposure to exotic sovereign credits is rising: how far into the high-yield space will they have to reach, and what will happen when markets turn?

“I’ve Seen the Future, Brother, it is Murder”

As the key driver of demand for frontier market bonds, the interest rate trajectory in developed space will also determine their future performance. This raises an almost philosophical question of the sustainability of negative rates trend and the prolonged period of low inflation we have observed globally since the 2008 crisis.

In a recent blog post PIMCO’s Joachim Fels argued that the phenomenon is not as absurd or freakish as some have made it out to be.

According to the investor, this stems from a number of intertwining factors, which could well lead to negative yields on US Treasuries in a very near future.

“What was once viewed as a short-term aberration – that creditors are paying debtors for taking their money – has already become commonplace in developed markets outside of the U.S – and US Treasuries may be no exception,” he explains.

Fels notes that longer life-spans across the developed world add more years to post-retirement, so more and more people demonstrate “negative time preference” – in other words, they start to value future consumption in retirement more than today’s (at the expense of borrowing to finance consumption today).

“To transfer purchasing power to the future via saving today, they are thus willing to accept a negative interest rate and bring it about through their saving behaviour,” he concludes.

But there are also downside risks. Nazli, among others, points to ongoing trade tensions between US and China putting a cap on further issuance from frontier and HY names. Capital Economics economists are also sceptical.

“The recent rally in frontier sovereign dollar bonds is unlikely to be sustained and we expect spreads to widen in Argentina, Ukraine and parts of the Middle East,” they explain in a recent research note.

Zielonka emphasises that there is a correlation between a recession and a migration to safety by investors. And economic turmoil in places like Argentina (and Turkey) pose a danger to their neighbours, like Paraguay, for example.

“Argentina is worth monitoring, it’s a leading candidate for a possible default in EMs; potential of a populist blowback is high, which would threaten the relationship with the IMF,” he points out in a note sent shortly before the recent primaries result. “Paraguay could find a way to isolate itself from the damage, but in the short term it will be hit hard by it.”

Bulgakov speculates that the next global downturn will be rooted in the influx of disruptive technologies affecting both the markets and industries across the board.

“The proliferation of easy money post-2008 generated a change of pace in development that’s higher than what we saw in the 50 years prior,” the banker notes.

But with the interest rates expected to stay low for the foreseeable future, investors are likely to continue reaching into the more remote pockets of the debt markets, focussing on diversifying currencies and tenors, and, on the longer horizon, exploring the nascent corporate markets among the weaker EMs.

“Even if the global economic outlook sours, some cash will of course flood back to safety, but some of it will stay in – the frontier markets are a real opportunity, and they aren’t going away,” Culverhouse affirms.

All of this, taken together, is making it much harder to parse how economic fundamentals and technical factors influence asset pricing, and as a result, buying behaviour. There is a high probability that much of the volatility seen in recent years is the result of these two camps of factors smashing against one another like waves against a cliffside. As long as monetary easing rules the day, it’s unlikely a blowout will emerge. But when the party does come to an end, as all parties do, the hangover is likely to hurt more, and for longer.